The Greek Worlds of the Eastern Mediterranean

At the dawn of the 19th century, the Eastern Mediterranean formed the core of the Ottoman Empire. Following decades of political processes and transitions, uprisings, revolutions, and in some cases the active intervention of colonial powers, the region by the mid-20th century came to consist of the following countries: Egypt, Greece, Jordan, Israel, Cyprus, Lebanon, Libya, Palestine, Syria, and Turkey.

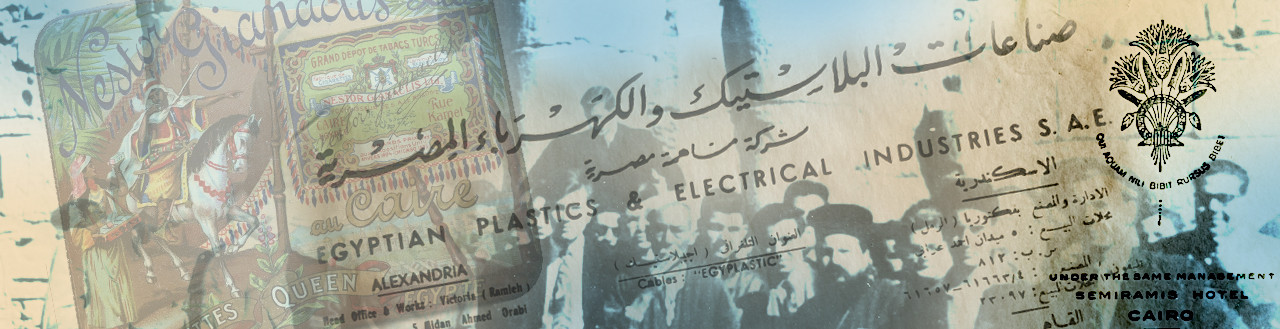

Both, along the coasts of the Eastern Mediterranean and in its broader hinterland, populations who often identified ethnically as “Greeks” or “Romaioi” and predominantly religiously as “Greek Orthodox Christians” lived—and in some cases, still live. However, there were also Greek Catholics and Protestants, as well as Greek Jews and Muslims. Their professional activities ranged from industrialists and large-scale merchants to office clerks, craftsmen, and unskilled laborers, with the majority of these Greeks belonging to middle and lower social classes.

The religiously and socially diverse “Greeks” who lived beyond the borders of Greece were not necessarily citizens of the Greek state, nor did they always regard Greece as their sole point of reference. They could be citizens of other European or Middle Eastern countries or even stateless individuals. For these people, Greek identity was often a fluid and shifting concept, mediated and shaped by communal and religious organizations as well as those linked to the Greek state.

For Greece, the broader Near East became the focal point of the “Great Idea” (Megali Idea) starting in the 1840s. This irredentist doctrine, rooted in the imagination of an imperial past harking back to the times of Alexander the Great and Byzantium, aimed at the “liberation” of Greeks who remained under Ottoman administration and the transformation of Greece into a new regional power.

The “Great Idea” was not only territorial but also economic, intellectual, and cultural in scope, representing primarily an imagined space with porous boundaries that could encompass various countries of the Eastern Mediterranean. This ambitious political program, along with its stark contradictions, was buried with the defeat of the Greek army in Asia Minor in 1922. Nevertheless, substantial Greek populations continued to reside in the region until the mid-20th century, and even today, some identify as “Greeks.”

The multifaceted Greek presence in the Eastern Mediterranean over the last two centuries prompts us to ask: what does it mean to be Greek in this region? The diverse interpretations and ongoing negotiations of the term “Greek” today position the area as a historical observatory for understanding the boundaries the concept can assume in both the contemporary and future Eastern Mediterranean and in Greece itself. In this evolving landscape, marked by new demographic realities and constant population movements, we are challenged to envision new forms of coexistence.